Will the blackbird population survive?

Joint press release from Sovon (the Dutch Institute for field ornithology), the DWHC, the Dutch Institute for Ecology and Erasmus Medical Center

The blackbird has been in the headlines many times over the last few weeks: Much like last year, there have been large numbers of reports of dead blackbirds, the majority of which are thought to be infected with Usutu virus. Furthermore, reports from dead birds have come from all over the country showing that the virus is spreading westwards – what impact will this have on the blackbird population?

The first outbreak of Usutu virus in the Netherlands was in 2016 and the virus resurfaced in April 2017. It predominantly affects blackbirds and at the beginning of September, Sovon and the DWHC had received more than 1500 reports of dead blackbirds.

Spread

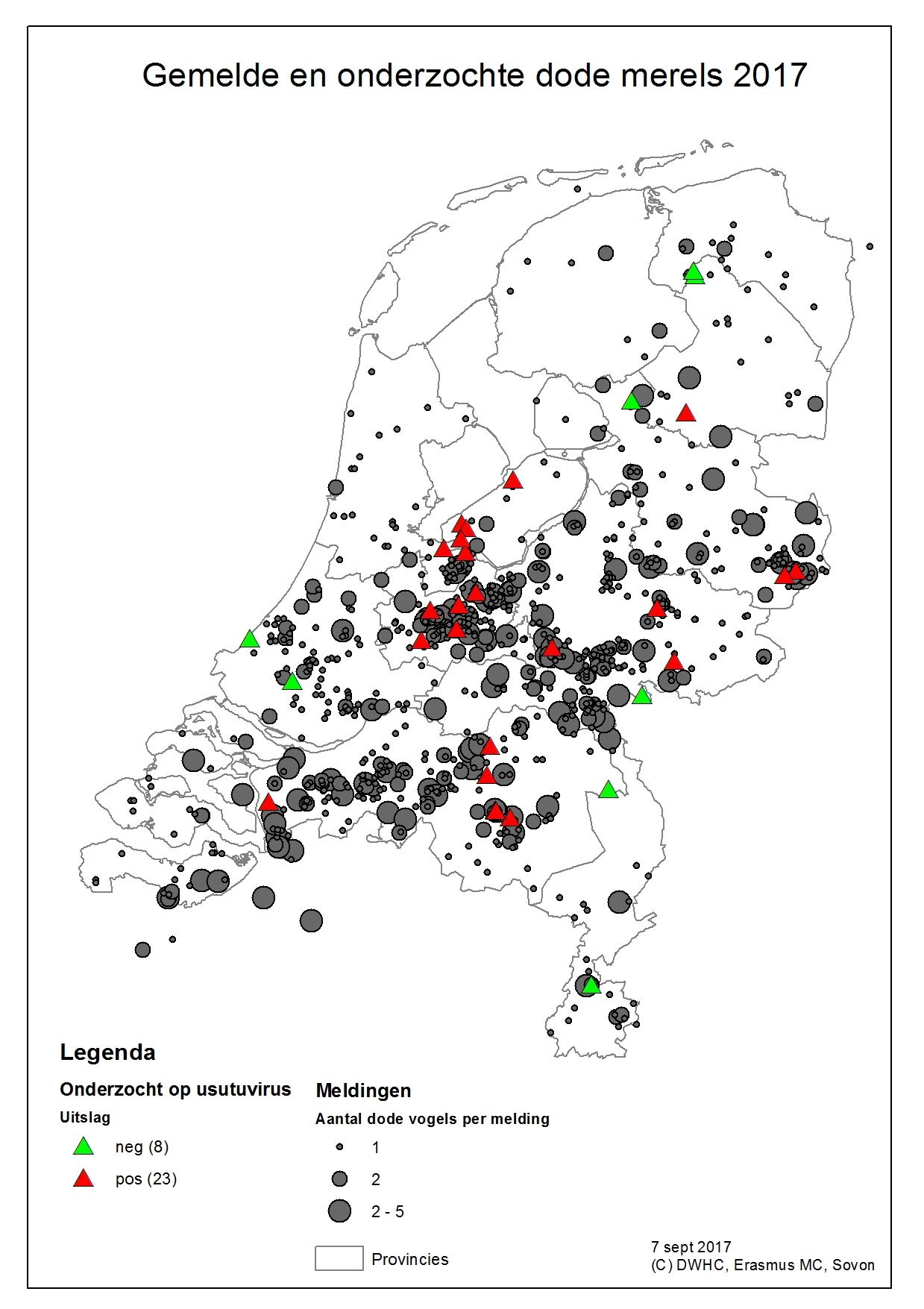

The majority of these reports have come from the central provinces of Gelderland, Utrecht and North Brabant. During the summer the virus appears to have spread to the West and Northeast.

Below is a map showing the locations of the reported dead blackbirds (green=not infected; red=infected)

Fewer blackbirds

These reports reflect the results from bird counts, however, a dip in numbers at the end of the summer is not, in itself, remarkable. Blackbirds are visibly active almost all year round; the song of the males can often be heard and with 2-3 broods per year they can often be seen on feeding flights, showing alarm behaviour and defending their territory. This changes abruptly when the last of the young have flown the nest and the moulting period begins.

It is normal that bird-counts such as the all-year garden bird-count indicated a decline in numbers from the end of July until early September, however, there is no doubt that the current numbers are particularly low as a result of Usutu virus. The average number of blackbirds per garden appears to be lower than normal this autumn: Interestingly, this effect was not seen following the 2016 outbreak.

Autumn migration

Numbers are likely to increase this autumn thanks to the autumn migration of the blackbird which peaks around the end of October. In general, Dutch breeding birds are non-migratory. The migratory birds that overwinter in the Netherlands tend to come from Scandinavia and North-Eastern Europe; the post-migratory increase in blackbird numbers does not, therefore, reflect an increase in the Dutch population.

Extent of the die-off

It is not easy to determine the exact extent of the die-off or to predict the impact of Usutu virus on the blackbird population in the long-term. It may only become clear in the autumn of 2018 whether the Dutch blackbird popluation has been seriously affected. Bird-counts and continued research are important for monitoring poulation dynamics. Studies with ringed birds have shown that birds that tested positive for Usutu virus at one capture appear to be healthy at re-capture.

Blackbird numbers

Blackbirds are found throughout the country and are possibly the most well-known garden bird. Large gardens with dense, bushy hedges for nest-building and lawns and meadows for foraging form an ideal habitat but blackbirds also frequent smaller urban gardens. The population of Dutch blackbirds has grown massively in the 20th century, reaching 900000-1200000 around the turn of the millenium. However, in recent years this growth appears to have stagnated.

Research

Different bodies are investigating Usutu virus. The Dutch field ornithology centre (Sovon) monitors (live and dead) bird numbers and distributions. The DWHC focuses on the study of disease in wildlife; and for virus research collaborates with the Erasmus Medical Center. The bird migration station of the Dutch Institute for Ecology follows ringed birds to monitor population dynamics and, together with Erasmus MC, investigates the incidence of Usutu virus in these birds.